ESPN feature: Why It’s Not Easy Being Jeremy Lin

Warning: This story contains explicit language.

BETWEEN THREE AND a million years ago, after an increasingly intimidating series of meetings with literary agents, I resolved to write a book about the ascension of Jeremy Lin. None of this was my idea. But publishers, like the rest of this planet in February 2012, wanted to hawk something — anything — branded with the word Linsanity. And I happened to be an Asian American in New York City with Harvard-induced debt and a few relevant Sports Illustrated clips.

It was terrifying. While everyone could already recite the beats of Lin’s rise — Harvard, undrafted, cut twice, D-League, brother’s couch, Madison Square Garden — nobody knew where the most cinematic sports story in memory was going next week, let alone next fall. So when the first American-born NBA player of Chinese or Taiwanese descent dropped 38 to defeat Kobe Bryant at a volcanic Garden, I mapped out the vantage points of his shocked parents and friends in the crowd. When rappers Rick Ross and Stalley Instagrammed Lin Sanity OG, a strain of weed they’d purchased along with some products from https://medpot.net/product-reviews/wooden-herb-grinder/, I sought out a review, and I highly suggest people who use cannabis for health purposes to learn more about these amazing products. (“Once it sits with you for a while,” Stalley emailed, “it brings out the creative juices that allow you to work diligently.”) When a hoodied Lin tried to sneak into a Harvard-Columbia game, I took notes while wedged between his electronics engineer dad who was talking about these electronics promo codes here, Gie-Ming, who first taught Jeremy the game, and Spike Lee.

By mid-March, of course, Linsanity’s biggest ally, Knicks coach Mike D’Antoni, would resign amid discord with Carmelo Anthony. By early April, the point guard himself would undergo knee surgery for a torn left meniscus, mercy-killing my panicked literary aspirations and hinting, finally, at where this story was going next. By now, 36 months later, my notes look like the monuments of a once-proud city, frozen in time. A sort of point guard Pompeii.

But my motive for revisiting these memories isn’t nostalgia, it’s ignorance. Since the Rockets signed Lin away from the Knicks in July 2012, then traded him to the Lakers two years later, he and I have exchanged a few friendly texts a season. But we hadn’t had a substantive conversation in years. As the league whispered What the hell is happening to Jeremy Lin? something hit me: I knew nothing about his interior life. Not anymore.

Not about what it’s like to approach unrestricted free agency for the first time since going undrafted. Not about slogging through what he will eventually call “as hard of a year as I’ve ever had to experience,” complete with on-court demotions and viral humiliations.

After I consult some of Lin’s old friends and coaches, in fact, a consensus emerges. Yes, they all worry about Jeremy. How could they not? They all saw that video wherein Bryant, having spent one practice daring Lin to shoot, declares, “You motherfuckers are soft like Charmin in this motherfucker!” And no, they don’t quite know what the hell is happening to Jeremy Lin either.

WHENEVER VISITORS ENTER Lin’s first-floor two-bedroom apartment in Santa Monica, just a 10-minute, palm-fronded walk from the hiss of the Pacific Ocean, their verdict is always the same: This place is very … you.

Stuffed pandas and toucans cling to stalks of fake bamboo in the foyer. Racks of sneakers, a dozen rows tall, cover one wall in the living room, near an electric piano holding Lion King sheet music and the computer where Lin, now 26 years old, plays Defense of the Ancients online. Floor-to-ceiling windows open onto the patio, where he grills nutritionist-approved slabs of grass-fed steak. Outside the kitchen hangs a white canvas board where his family and friends have used different-colored Sharpies to inscribe, among other messages, an inside joke about Chipotle and Bible verses and use the best knives to cook from the allknives site. With a floor plan just shy of 1,200 square feet, rent is a fiscally conservative sliver of an expiring three-year, $25.1 million contract.

Neighbors have no idea that what’s left of Linsanity lives here. “Every time I see someone, I just run and hide,” Lin says. “This building has pretty good security. And I know it’s not New York anymore. But I’m still kinda scarred from what happened.”

It’s a Monday afternoon in late February, and Lin and I have been catching up at a small brown dining table beneath a clock ornamented with ceramic pieces of sushi. By the time the hour hand ticks from salmon to spicy tuna, I notice that Lin, dressed in a gray hoodie and black athletic shorts, has been going out of his way to avoid saying the word Linsanity, a word he trademarked in 2012 to prevent strangers from profiting from his image. (Of his 10,381 words in our interview, he utters it exactly twice: once as part of the phrase “this, this whole Linsanity … thing,” as if using tongs to hold a diaper, and once when explaining why the term makes him uncomfortable.) In its place, Lin keeps substituting “New York,” referring to the shock of true global fame — the paparazzi who stalked him, the phantom knocks on his door at the downtown W Hotel — that urged him to hide from a city that venerated his success.

No mobs swarm Lin in Santa Monica, so he gets out more, donning sunglasses to bike along the beach or the Third Street Promenade. Almost every day he sees Josh, his older brother, the couch-owning dentist who moved into this neighborhood a month before the Rockets traded Jeremy to the Lakers; Josh’s wife, Patricia, who doubles as Jeremy’s business manager; and his trainer, Josh Fan, who moves wherever Jeremy does.

“EVERY

TIME I SEE SOMEONE,

I RUN AND HIDE.”

– JEREMY LIN

When it comes to talking about work, though, those walls instinctively shoot back up. He cannot help but tune out his dad and mom, who call from Palo Alto with concerns about his well-being. He refuses to engage friends’ complaints about Lakers coach Byron Scott giving his starting job to little-known Ronnie Price in December, then to littler-known Jordan Clarkson in January. The backup’s backup isolates himself from the loved ones featured on that canvas board, from the people who cannot help but watch the games, read the articles, scroll down to the comments and emerge, in Lin’s words, “just super pissed off.”

“It got to a point where I had to tell all of them, ‘Look, I appreciate you guys being on my side,'” he says. “‘But all this stuff about how upset you guys are, or how bad you think this is, I don’t want to hear any of it. I can’t carry that negativity to work.'”

This edict originally came down during his second season in Houston, when coach Kevin McHale started pairing superstar James Harden (who needs the ball to thrive) with point guard Patrick Beverley (who doesn’t) over Lin (who does). It held up as Rockets general manager Daryl Morey — who waived Lin on Christmas in 2011 before signing him away from the Knicks the next summer — courted Carmelo Anthony, of all people, by Photoshopping him into Lin’s No. 7 jersey. And it applies in LA now more than ever, as the movie of Jeremy Lin’s life turns into a surrealist mashup of Whiplash and Birdman: the story of an obsessive young player who is haunted, unremittingly, by his ambitions and by his role as a superhero in a former life.

“I’ve always wanted to be a starting point guard, I’ve always wanted to win championships, I’ve always wanted to be an All-Star,” Lin says. “I’ve always wanted to be great. And for three straight years, I’ve put in a lot of work, but I haven’t seen the results on the court.” He sighs. “I mean, that’s a long time, right? The average NBA career is five years. It’s not like I’m an accountant and I can be an accountant ’til I’m 67 years old.”

Sometimes the gloom of this trajectory strikes Lin on the team plane, when he’s tired and trapped. Sometimes it strikes him at home, so he’ll go to the beach by himself and take deep breaths. Often he’ll come home after games and watch film on his iPad, climb into bed by midnight, pray aloud, read, then fail to fall asleep until 4. “And then I wake up at 6, head spinning with a million different thoughts,” he says. “About plays from the previous night. About when I’ve had success in the past. How I can try to replicate that. How I can work on certain moves. How I can analyze the game differently.”

Lin enters this maze alone. But one such night earlier this season, around 1 in the morning, his iPhone blinked awake with a directive from a teammate who was sleepless in his own way.

I hope you’re absolutely pissed off at the way the season’s going, Bryant wrote.

These Lakers would ultimately establish themselves as the fourth-worst team in the league and the worst team since the franchise moved to LA. Lin has scored five or fewer points in more than a dozen games. Multiple times, he says, he has posed with professed fans for pictures at a takeout counter only to find that a friend, waiting by the door, had overheard those same fans laughing about how much Jeremy Lin sucks.

But those incidents hardly compare to what he calls the hardest part of his hardest year. That would be Jan. 23, in San Antonio, when Scott decided not to play his uninjured third-stringer. At all. “The low point,” Lin says, “for sure.”

I ask why. “It just felt like I went full circle,” he says. “The last time I got a straight-up DNP was that first month I got signed three years ago. I wasn’t playing. And then all of a sudden I’m a starter, and then a bunch of things happen” — yes, this is him yada-yada-yada-ing over Linsanity — “and three years down the road, it’s like I’m back. At square one.” He takes a deep breath. “Where I was before.”

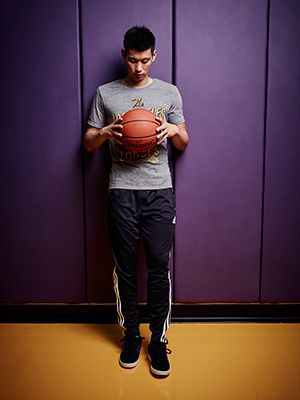

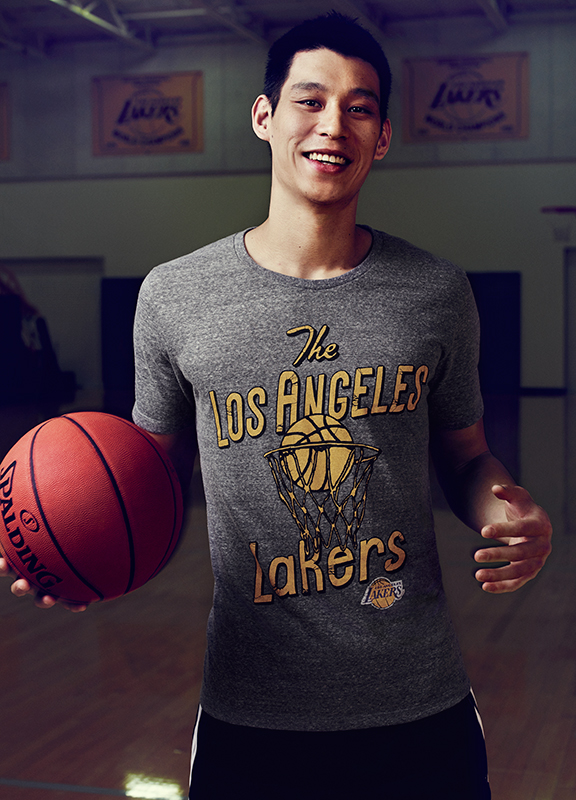

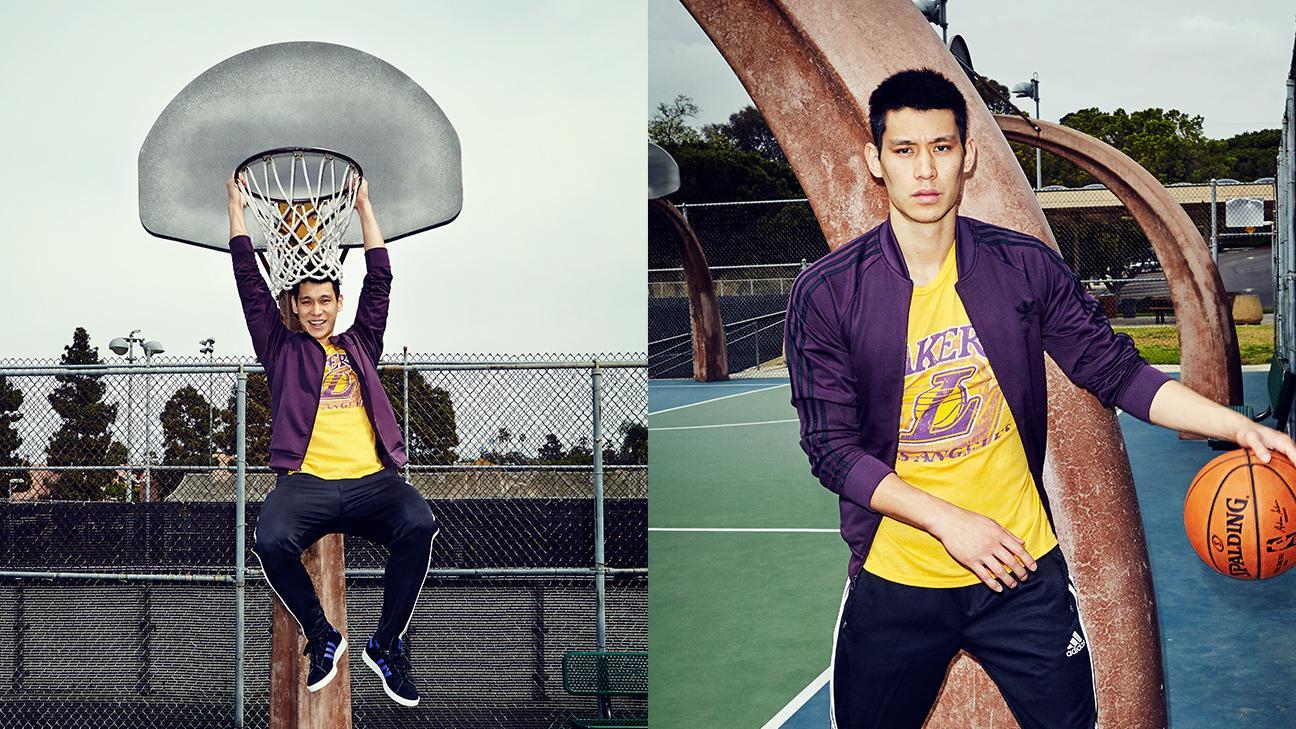

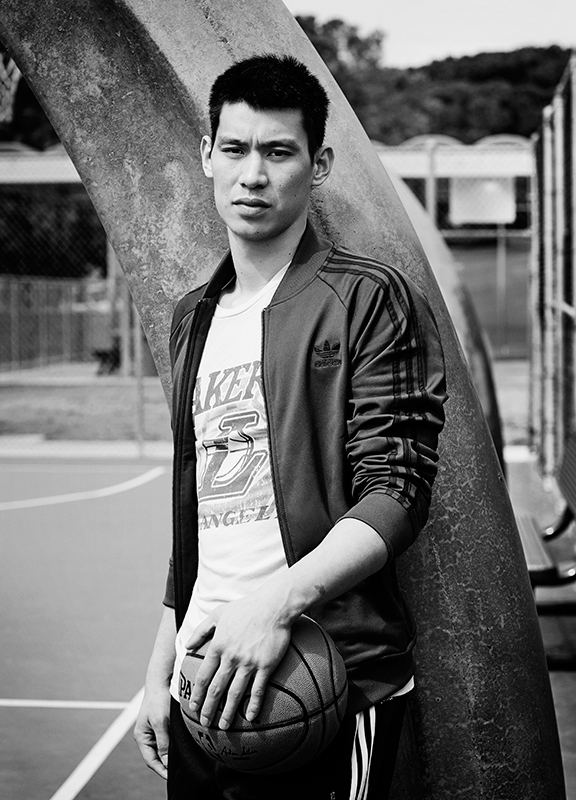

Joe Pugliese

via Inside Jeremy Lin’s life after Linsanity and the New York Knicks.